Dining Philosophers

01 Nov 2024Introduction

The dining philosophers problem is a classic synchronization and concurrency problem in computer science, illustrating the challenges of managing shared resources. In this post, I’ll walk through an implementation of the dining philosophers problem in Rust, explaining each part of the code to show how it tackles potential deadlocks and resource contention.

You can find the full code listing for this article here.

The Problem

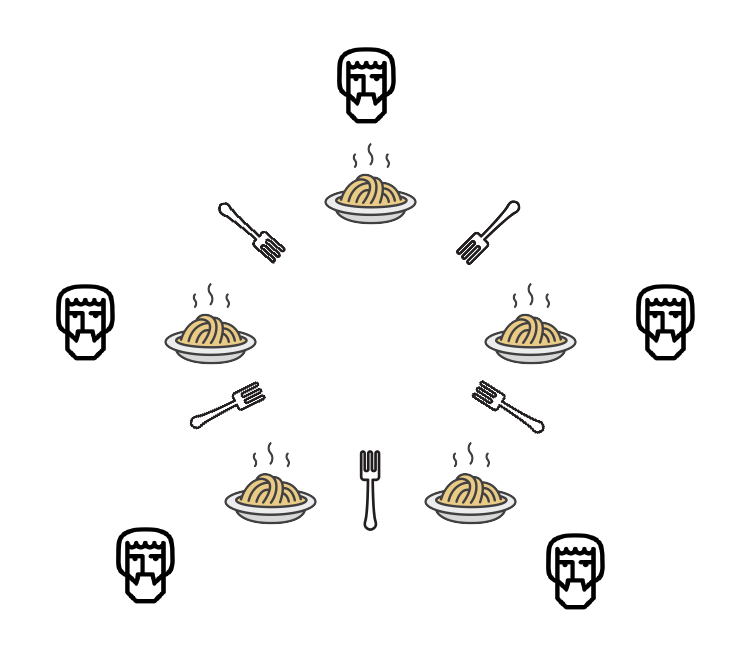

Imagine five philosophers seated at a round table.

Between each philosopher is a fork, and to eat, each philosopher needs to hold the fork to their left and the fork to their right.

This setup leads to a potential deadlock if each philosopher picks up their left fork at the same time, preventing any of them from picking up their right fork.

To avoid this deadlock, our implementation uses randomized behavior to increase concurrency and reduce contention for resources.

Solving the Problem

The Philosopher

First of all, we need to define a Philosopher:

struct Philosopher {

name: String,

left: Arc<Mutex<i8>>,

right: Arc<Mutex<i8>>,

eaten: Arc<Mutex<i32>>

}namegives this Philosopher a name on screenleftandrightare the two forks that this Philosopher is allowed to eat witheatenis a counter, so we can see if anyone starves!

Arc<Mutex<T>>

left, right, and eaten are all typed with Arc<Mutex<T>>.

We use Arc<Mutex<T>> to share resources safely across threads. Arc (atomic reference counting) allows multiple

threads to own the same resource, and Mutex ensures that only one thread can access a resource at a time.

Implementing the Philosopher Struct

We can simplify building one of these structs with a new method:

impl Philosopher {

fn new(name: &str, left: Arc<Mutex<i8>>, right: Arc<Mutex<i8>>) -> Self {

Philosopher {

name: name.to_string(),

left,

right,

eaten: Arc::new(Mutex::new(0)),

}

}Dining

We now want to simulate a Philosopher attempting to eat. This is where the Philosopher tries to acquire the forks needed.

We do this with the dine function.

fn dine(&self) {

let mut rng = rand::thread_rng();

loop {

// Randomize the order in each dining attempt

let reverse_order = rng.gen_bool(0.5);Using a random number generator (rng), each philosopher randomly decides in which order to try to pick up forks. This

randomness reduces the chances of all philosophers trying to grab the same forks simultaneously.

Finding a Fork

The philosopher selects which fork to pick up first based on the randomized reverse_order.

let left_first = if reverse_order {

&self.right

} else {

&self.left

};

let right_second = if reverse_order {

&self.left

} else {

&self.right

};Here, if reverse_order is true, the philosopher picks up the right fork first; otherwise, they pick up the left fork

first.

Attempting to Eat

To avoid deadlock, the philosopher only eats if they can successfully lock both forks. If both locks are acquired, they

eat, increment their eaten counter, and release the locks after eating.

if let Ok(_first) = left_first.try_lock() {

if let Ok(_second) = right_second.try_lock() {

println!("{} is eating ({})", self.name, *self.eaten.lock().unwrap());

// Update eating counter

if let Ok(mut count) = self.eaten.lock() {

*count += 1;

}

thread::sleep(Duration::from_millis(1000));

println!("{} has finished eating", self.name);

} else {

println!("{} couldn't get both forks and is thinking", self.name);

}

} else {

println!("{} couldn't get both forks and is thinking", self.name);

}If either lock fails, the philosopher “thinks” (retries later). The use of try_lock ensures that philosophers don’t

wait indefinitely for forks, reducing the chance of deadlock.

After eating, a philosopher sleeps for a random time to avoid overlapping lock attempts with other philosophers.

thread::sleep(Duration::from_millis(rng.gen_range(100..500)));

}

}Sitting Down to Eat

Now we set the table, and get the Philosophers to sit down.

fn main() {

let forks: Vec<Arc<Mutex<i8>>> = (0..5)

.map(|i| Arc::new(Mutex::new(i)))

.collect();

let philosophers = vec![

Philosopher::new("Jane", forks[0].clone(), forks[1].clone()),

Philosopher::new("Sally", forks[1].clone(), forks[2].clone()),

Philosopher::new("Margaret", forks[2].clone(), forks[3].clone()),

Philosopher::new("Kylie", forks[3].clone(), forks[4].clone()),

Philosopher::new("Marie", forks[4].clone(), forks[0].clone()),

];Each philosopher is created with the forks on their left and right. The Arc wrapper ensures each fork can be safely

shared across threads.

let handles: Vec<_> = philosophers.into_iter().map(|p| {

thread::spawn(move || {

p.dine();

})

}).collect();

for handle in handles {

handle.join().unwrap();

}

}Each philosopher’s dine function runs in its own thread, allowing them to operate concurrently. The main thread then

waits for all philosopher threads to finish.

Results

Your mileage may vary due to the random number generator, but you can see even distribution between the Philosophers as the simulation runs. For brevity, I stripped all the other messages out of this output.

Jane is eating (0)

Kylie is eating (0)

Marie is eating (0)

Margaret is eating (0)

Kylie is eating (1)

Sally is eating (0)

Jane is eating (1)

Margaret is eating (1)

Sally is eating (1)

Marie is eating (1)

Margaret is eating (2)

Jane is eating (2)

Margaret is eating (3)

Marie is eating (2)

Margaret is eating (4)

Jane is eating (3)

Kylie is eating (2)

Sally is eating (2)Conclusion

This implementation uses randomized fork-picking order and non-blocking try_lock calls to minimize the risk of

deadlock and improve concurrency. Each philosopher tries to acquire forks in different orders and backs off to “think”

if they can’t proceed, simulating a real-world attempt to handle resource contention without deadlock.

This approach highlights Rust’s power in building concurrent, safe programs where shared resources can be managed

cleanly with Arc and Mutex. The dining philosophers problem is a great example of Rust’s capabilities in handling

complex synchronization issues, ensuring a safe and efficient solution.